Chainmail math 1: a weave is a path component of the (coarse moduli) space of weaves

This post is the first of a stream-of-conciousness series on chain mail math, and in particular, on classification problems for weaves of chainmail. There is no intended audience, but if all is right in the world, the important bits will be accessible to individuals possessing a working knowledge of basic topology, algebra, and category theory; if you do not know what the homotopy groups of a topological space are, consider that to be the main prerequisite at this time.

At some point in time, I plan on making a document summarizing the work which is accessible to the topology-curious chainmailler.

What chainmail really is, and what a unit weave ought be

Throughout many regions of the world and many times in history, people have been inspired to make protective garments (armor, butcher gloves, etc.) out of an interlinked collection of small metal pieces, each in the shape of a solid torus. Such garments are examples of chainmail; roughly, we may consider chainmail to be the craft wherein one interlinks metal solid tori.

Through this definition, we see that fabricating traditional chains with circle components can be considered chainmail; in fact, using the traditional armor weave of European-4-in-1, one may see that a plane of European armor is crafted placing a solid torus at each point in a lattice, and if we restrict this construction to two adjacent rows, we recover a traditional 2-in-1 chain, up to physical manipulation. Hence we may view European 4-in-1 armor as a line’s worth of interlocking chains.

Advancing to the past few decades, perhaps growing out of ren fairs, another craft has emerged under the name “chainmail:” nowadays people craft jewelry out of more complicated and varied patterns of interlocking metal solid tori. These often take the form of units, which are attached to a necklace chain as a pendant or to an earwire as an earring.

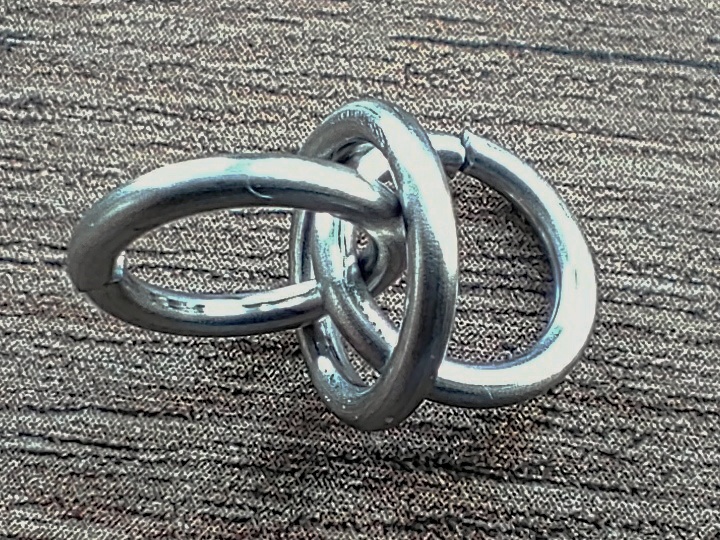

A self-stable vortex medallion, strung along a chain of Jens Pind linkage.

It is these units, initially, that we’re interested in classifying. So we may begin by asking an incorrect question:

Incorrect question 1. What are the ways of isometrically embedding finitely many solid tori into \(\RR^3\)?

One reason this is incorrect is that it has a tautological answer which is uncountably infinite: there is one for every isometric embedding \(\coprod_n T_i \rightarrow \RR^3\), where \(T_i\) is a standard solid torus of a given inner radius and “wire” radius! This is not of interest, and it doesn’t help us work with chainmail in practice.

Another reason this is incorrect is that it appears to distinguish between weaves which are secretly the same; if I have a generic piece of chainmail, then I can easily deform it to represent an uncountable collection of distinct weaves. This is a bit encouraging: we have uncountably many weaves with uncountable overcounting. We can attempt to rectify this:

Incorrect question 2. What are the ways of isometrically embedding finitely many solid tori into \(\RR^3\) up to “physical deformation?”

I’ve called this incorrect for a reason: this still uncountably overcounts! To explain why, I’ll introduce a bit of specific terminology.

In chainmail, there is a (redundant) list of three measurements which specify the geometry of a jump ring: the inner diameter (diameter of the smallest longitudinal circle), the wire diameter (diameter of the largest meridian), and the aspect ratio (inner diameter divided by wire diameter). My preferred way of referring to rings is by wire diameter and AR, so that for single-AR designs, I can dialate my specification of the design with a single datum.

We overcount because we any two weaves made of rings of different ARs are considered non-equivalent: for instance, given a weave made of rings of core diameter \(1\) (i.e. inner diameter \(+\) half wire diameter is \(1\)) and a fixed AR \(A\), I can form another “weave” of rings of core diameter \(1\) and AR \(A + \varepsilon\) by “shrinking” each ring.

Our classification should identify weaves which are related by this procedure; we might as well shrink rings to infinitesimally small, and note that as \(A \gg 0\), weaves become idenfied with AR \(A\) iff they’re identified with AR \(A + \varepsilon\). I’ll skip the ponderance of the (co)limit of the procedure, and say what we get:

Correct question 1. What are the ways of “rigidly” embedding finitely many circles into \(\RR^3\) up to deformations of rigidly embedded circles?

However, in chainmail, there are sometimes phenomena that we care about which are specific towards ID relationships, called captivation and orbiting; a circle is captivated if it spans a plane not intersecting any other circles, yet it is not able to be “separated” from the rest of the weave to occupy disjoint isometrically embedded standard balls. Similarly, a circle orbits another part of the weave if it is unlinked to the part, yet it is not able to be freed from that part intersecting its disk.

The following weave exhibits this orbital behavior:

The unlinked torus can’t escape so long as it’s ID is at most the outer diameter of the rings in the linking which it orbits. however, if it’s ID is any amount larger than the OD of the surrounding ones, it is free.

We can manage some ID specific interactions in a finitary classification if we fix ratios; the simplest example is weaves of rings which all have the same ID:

Correct question 2. What are the ways of “rigidly” embedding finitely many unit circles of radius 1 into \(\RR^3\) up to deformations of rigidly embedded unit circle?

It is this question that we endeavor to answer. We now define “weave” in a precise way, to capture the answer to this question. However, first, we need a bit of technology.

Graded spaces

We briefly mention the relevant technology of graded spaces. The non-technical reader may safely consider a graded space to be a sequence of spaces, and ignore the details of this technology altogether.

Definition 1. The category of graded spaces is the functor category \(\mathbf{Top}^{\ZZ} = \operatorname{Fun}(\ZZ,\mathbf{Top})\), where \(\ZZ\) has been regarded as the objects of a category with no non-identity morphisms. Endowing \(\ZZ\) with a symmetric monoidal structure via addition of integers, graded spaces are endowed with a day convolution symmetric monoidal structure; this is explicitly computed on objects by

$$\prn{X_* \otimes Y_*}_n = \coprod_{i + j = n} X_i \times Y_j.$$

Graded spaces can be endowed with the structure of a topological or simplicially enriched cat by replacing giving \(\ZZ\) the discrete topology and replacing the \(\mathbf{Set}\) enriched category with one enriched in an appropriate category. Alternatively, we may directly consider the symmetric monoidal \(\infty\)-category of graded spaces by taking the functor \(\infty\)-category \(\mathcal{S}^{\ZZ}\), where \(\mathcal{S}\) is the \(\infty\)-category of spaces. This may be too morally correct for such an explicit and messy goal.

When regarded as a topologically enriched cat, \(\mathbf{Top}^{\ZZ}\) is tensored, where \(\prn{S \otimes X_*}_n = S \times X_n\). This yields a functor \(\operatorname{Op}(\mathbf{Top}) \rightarrow \operatorname{Op}\prn{\mathbf{Top}^{\ZZ}}\) which is computed on objects by replacing the space of \(j\)ary operations with a graded space of \(j\)ary operations concentrated at degree zero, whose underlying space is the original operations. In particular, standard models for \(\EE_n\) in \(\mathbf{Top}\) tensor to models in graded spaces.

The (graded) space of chain mail weaves

We hope to define a graded space \(\cW_*\), such that \(W_n := \pi_0 \cW_n\) is the correct notion of a weave with \(n\) components. Formally, let’s write \(\cW_0 = \cbr{*}\), i.e. there is a space of 0-component weaves consisting of precisely one point. We may first endeavor to define \(\cW_1\) correctly.

These are meant to be rigidly embedded circles of radius 1 in \(\RR^3\). Every such circle is a uniquely a unit circle in an embedded (pointed) plane, which is linearly embedded in \(\RR^3\). We may use this as a definition:

Definition 2. \(\cW_1 := \RR^3 \times \RRP^2\).

This is scary if not unpacked: already we’re working with a non-orientable 5-manifold! However, as we currently only care about \(\pi_0 \cW_n\), we should only really care about \(\cW_1\) up to homotopy equivalence; up to equivalence, we have \(\cW_1 \simeq \RRP^2\) (we can pull ring center to the origin up to to contractible ambiguity), which ought be one of the least scary non-orientable surfaces.

For those who seek only to track equivalence classes of weaves, and not the equivalences themselves, we may note that \(W_1 := \pi_0(\RRP^2) = \cbr{O}\), where \(O\) is a weave of one component; this truly is simple!

Let’s go one \(n\) levels up: what ought the space of two-component weaves be? One good answer for this is the space of tuples of circles which are nonintersecting.

Let’s flesh this all the way out:

Definition 3. The \(n\)th part of the space of chainmail weaves is defined by

$$\cW_n := \cbr{\cbr{x_i,P_i}_{i \in [n]} \mid \not \exists i\neq j \text{ with } y \in P_i \cap P_j \text{ s.t. } d(x_i,y) = d(x_j,y) = 1)} \subset \prn{\RR^3 \times \RRP^2}^n_{\Sigma_n};$$

explicitly, this is the space of \(n\) nonintersecting circles in \(\RR^3\).

As said before, we define \(W_n := \pi_0 \cW_n\). We also write \(\cW := \coprod_{n \in \NN} \cW_n\) and \(W := \pi_0 \cW = \coprod_{n \in \NN} W_n\). With this, we can finally say what a weave is:

Definition 4. A chainmail weave is an element of \(W\). A weave has \(n\) components if it’s an element of \(W_n\).

A nod towards further work

We now briefly summarize future directions for the classification of chainmail weaves. Generally, we refer to the problem of defining a bijection \(C_n \rightarrow W_n\) with \(I_n\) of finite type as the weave classification problem; finding such a surjection is the exhaustion problem, and finding an injection \(W_n \hookrightarrow I_n\) into a finite type graded set is the distinction problem.

To solve the classification problem, one may equivalently (in some sense) simultaneously solve the exhaustion and distinction problems. Our work will involve many reductions, some to each of these 3 problems.

Let \(\Fr_3(X_*)\) refer to the free \(\EE_3\) algebra in graded spaces generated by \(X_*\). Our first reduction, this time to the classification problem, is a form of primary decomposition; given two weaves \(w,w' \in W\), there is a well defined weave \(w + w'\) given by placing the weaves “next to each other.” We will show that this operation is the \(\pi_0\)-induced commutative monoid corresponding with an \(\EE_3\) algebra structure on \(\cW_*\), and we will construct a graded summand of “prime weaves” \(\widetilde{\cW}_*\) such that the associated \(\EE_3\)-morphism \(\Fr_3(\widetilde{\cW}_*) \rightarrow \cW_*\) is a \(\pi_0\)-isomorphism; as a corrolary, \(W_*\) will be shown to be a tensor algebra (in graded sets).

Our second reduction will be the construction of nontrivial graded spaces \(\cA_*\), \(\cA^\vee\), and \(\cW^\vee\), together with a formula that expresses \(\cW_*\) in terms of them. The graded spaces \(\cT_*, \cA_* \subset \cW_*\) embed as the subspace which is the union of the \(n\)-Möbius and \(n\) parallel components, and those with no such proper nontrivial subweaves lying within an embedded solid torus of core radius 1 (the atoroidal weaves). A \(\vee\)-superscript corresponds with a space of embeddings of weaves into a solid torus of core radius 1.

This is written in terms of the symmetric spaces: a symmetric space is a functor \(\coprod_n \Sigma_n \rightarrow \operatorname{Top}\). These have a day convolution monoidal product, a “composition product” (for which monoids are precisely the operads), and a functor \((-)_{\Sigma}:\Top^\Sigma \rightarrow \Top^\ZZ\) whose \(n\)th level is computed by \((X_\Sigma)_n = X(n)_{\Sigma_n}\). We generally write \(\cW^{\operatorname{sym}}\) for the obvious symmetric sequence satisfying \(\cW^{\operatorname{sym}}_{\Sigma} = \cW_*\).

There is a natural structure of \(\cW^\vee\) as an operad under substitution; toroidal decomposition is a realization of \(\cW^\vee\) as a summand of a free operad

$$\cW^{\vee} \hookrightarrow \cO_{\cA^{\vee}} \circ \cT^{\operatorname{sym}},$$

together with an expression of \(\cW^{\vee}\) as an explicit suboperad and quotient operad, whose data are expressed in terms of known chain mail weaves. This is proved on path components, and the equivalence on homotopy groups is conjectural. We further conjecture a result

$$\cW^{\operatorname{sym}} \simeq \cA^{\operatorname{sym}} \circ \cW,$$

which has also been proved on path components. The upshot of this is that it provides a formula for \(W\) which only references the set of atoroidal weaves; in the RIM, many of the listed 4-component weaves are obviously not atoroidal (JPL3, satellite, Mobius 4, Japanese triangle, Tetra, Orbit, Cross Orbit, and Apogee), so this seems to already kill a good deal of redundancy on level 4.

For distinction, it is notable that all of the weaves in the RIM are distinguished by taking the underlying link; this is not true for prime atoroidal weaves at level 5, so we will need to find non-topological invariants to solve the distinction problem at that level.

Forward references

-

On primary decomposition: every weave decomposes uniquely into simpler weaves called primary weaves, which can’t be expressed as two separate weaves placed next to each other.

-

The classification of weaves with 2 or fewer components: there is a unique prime weave of 2 components.

-

Toroidal decomposition, the content and the formalism; every weave is canonically generated from the one ring by repeatedly replacing rings with atoroidal weaves, up to ambiguity generated by the two ways of generating the 3-Möbius and 3-adjacent-ring weaves.

-

A definition for weaves which replicate in one direction, precise and intuitive.

-

A more general definition for weaves which respect an arbitrary group action.

The following are articles hopefully to come:

-

An exhaustion via weave diagrams: \(W_n\) is finite, and an algorithm to compute it.

-

The level 3 classification: there is a unique atoroidal weave of 3 components, and two toroidal primary ones.

-

The level 4 classification: The RIM is correct.