Categorical structures on the l-pieces part 2

In this post, my goal is to describe the category theory concept underlying the \(\ell\)-pieces. This is a construct called \(n\)-fold categories, the more complicated and less useful cousin of \(n\)-categories. I’ll mostly focus on the \(n=2\) case of double categories, since they generally seem more studied. Then, I’ll give a notion of sqaure tangles which runs parallel to the study of pieces, but is a lot easier to work with. In a future post, I’ll bring \(\ell\)-pieces back.

This’ll mostly be a restatement of \(n\)Lab plus some personal thoughts. We’ll be mostly concerned with the simple structure of \(n\)-fold categories; if you’re interested, there is some present work being done by Moser, Sarazola, and Verdugo on Quillen model structures on the category of double categories, but this is irrelevant, so I won’t mention it further.

See part 1 here, and see part 3 here.

What an \(n\)-fold category is

Recall that (modulo size issues) an \(n\)-category is simply a category enriched in the \((n-1)\)-categories. I’ll give a similar definition for \(n\)-fold categories, but to do so I’ll give a little bit of exposition on internal categories. The notation will follow MacLane’s “Categories for the working mathematician.”

Definition. Let \(\bE\) be a category. A category internal to \(\bE\) is the following data

-

an object of objects \(C_0 \in \bE\),

-

an object of arrows \(C_1 \in \bE\),

-

an identity arrow \(i:C_0 \rightarrow C_1\),

-

domain and codomain arrows \(d_0,d_1:C_1 \rightarrow C_0\), and

-

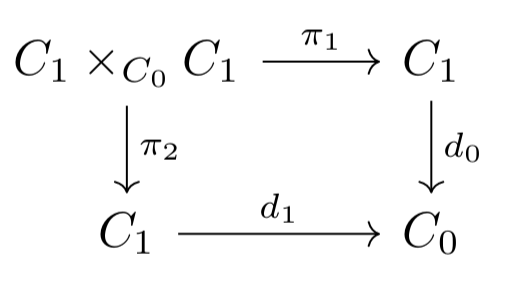

a composition arrow \(\gamma:C_1 \times_{C_0} C_1 \rightarrow C_1\) defined on the pullback:

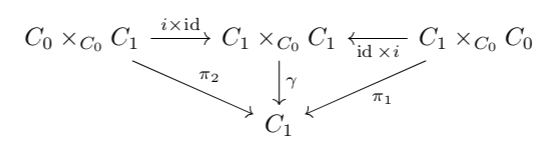

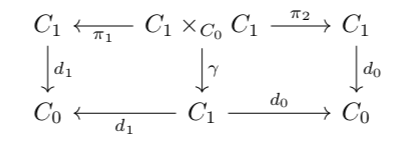

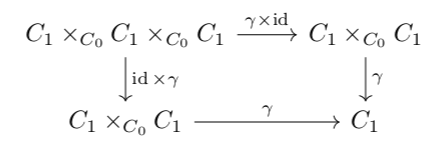

such that \(d_0i = \id = d_1i\) so that identity arrows have the right (co)domain and such that the following diagrams commute, establishing identity, (co)domain of the composite, and associativity of composition.

We can define internal functors in exactly the way one expects; they are pairs of morphisms between the object and arrow objects which are compatible with the above data. Hence there is a well-defined notion of a category of internal categories in \(\bE\).

This implicitly requires that the pullback \(C_1 \times_{C_0} C_1\) exists, as well as a few others. In the case that \(\bE\) has all pullbacks, an internal category can be shown to be precisely a monad in the bicategory of spans in \(\bE\), though I won’t go into depth (see nlab for details).

We’ll handwave existence of pullbacks away, since we only work with finitely complete categories.

In fact, the following theorem due to Charles and Andrée Ehresmann (and which appears directly proven in nlab) let’s us handwave this away.

Theorem. Suppose \(\bE\) is finitely complete. Then, the category of internal categories in \(\bE\) is also finitely complete. The same applies for finitely complete cartesian closed categories.

When \(\bE = \mathbf{Set}\), the internal category axioms are precisely the axioms for an ordinary category; hence a (small) category is simply a category object in \(\mathbf{Set}\). You can probably guess where this is going…

Definition. A 1-fold category is simply a small category. An \(n\)-fold category is a category internal to the category of \((n-1)\)-fold categories.

This is neat, but perhaps uninformatively so. Now, I’ll go into detail on how to picture these, with a heavy focus on double categories.

What an \(n\)-fold category really is

Let’s draw a double category \(D_1 \rightrightarrows D_0\). Such a category may be said to consist of the following:

-

objects given by the objects of \(D_0\).

-

vertical morphisms given by the morphisms of \(D_0\).

-

horizontal morphisms given by the objects of \(D_1\).

-

2-cells given by the morphisms of \(D_1\).

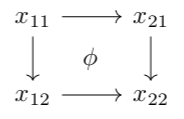

This can be pictured via the following square:

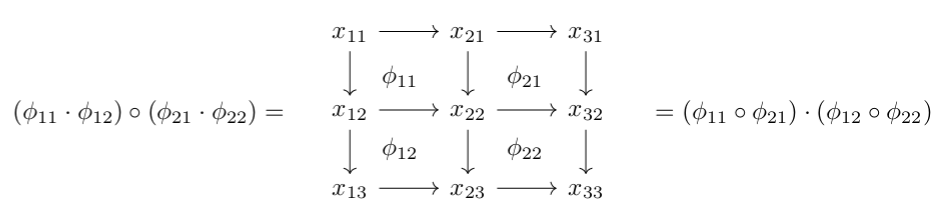

The data of a double category may be summarized by horizontal and vertical “edge categories,” as well as horizontal and vertical “2-cell categories” which are compatible with the edge categories and satisfy the interchange law specifying that the following composite is well-defined.

We will prefer this type of description, as it shows symmetry; there is an evident transpose double category given by interchanging the vertical and horizontal direction. There exists a Poincaré dual calculus of string diagrams for double categories, due to Myers, but we won’t think too hard about that, in part because I’m not sure the same exists for \(n\)-fold categories.

The reader can take it upon themself to work through an analogous construction of \(n\)-fold categories being built up from \(n\)-dimensional hypercubes, where a pair of opposing \(m\)-dimensional facets in an \((m+1)\)-dimensional face describes an \(m\)-fold category; i haven’t formalized this, but I’m fairly certain that any permutation on \(n\) letters can transform an \(n\)fold category into another one by permuting the opposin pairs of facets. This is not the relevant kind of abstract nonsense, so I mention it only in passing.

The square tangles as a double category with one object

There’s some extra niceness that comes along with higher category theory for whom most of the structure is simple; for instance, a category with one object is a (small) monoid, and a 2-category with one object is a (small, strict) monoidal category.

There’s an analogous but unfamiliar structure to a one-object double category, which appears as a pair of horizontal and vertical monoids and a set of crossed morphisms with horizontal and vertical composition which are compatible with the horizontal and vertical monoids, which are each monoidal, and which satisfy an interchane law. This structure was described in this this math stackexchange post.

The square tangles will be defined with precisely this structure, and later a broader class of \(\ell\)-pieces will be defined with a similar triviality for \(\ell\)-fold categories.

Definition. Let \(R\) be the square, and let \(\partial R = \bigcup_{i=1}^{2} F_{1i} \cup F_{2i}\) be the decomposition of the boundary of the square into two pairs of opposing edges. We define a square tangle to be a tangle in \((R,\bigcup F_{ij} - \bigcup F_{ij} \cap F_{kl})\). Doubling this individually across each pair of faces yields a link in a thickened torus; if this link is hyperbolic, we say that the square tangle is hyperbolic.

Two square tangles with the same number of endpoints on opposing edges have a clear notion of vertical or horizontal composition done by gluing, depending on which edges are being glued together.

It’s a consequence of the main theorem of the forthcoming paper that a link which subdivides into a hyperbolic square tangle is hyperbolic, and a square tangle which decomposes into two hyperbolic square tangles is hyperbolic. There are lower bounds on volumes going along with that, but we won’t worry too much. I’d rather give a double category.

Definition. We define the double category \(\STan\) by the following data:

-

there is a single object \(*\).

-

the horizontal and vertical edge monoids are each given by \(\NN\) under addition.

-

the set of 2-cells is given by the square tangles, where the top and bottom edges are given by the number of endpoints on \(F_{11}\) and \(F_{21}\), and similarly the left and right edges are given by the number of endpoints on \(F_{12}\) and \(F_{22}\).

-

composition of 2-cells is given by the composition of square tangles.

Interchange is clear, as it follows by associativity of “topoloical gluing.” The vertical identity \(2\)-cell \(\id_n^\cdot\) is given by the square tangle with \(n\) uncrossing vertical strands; the horizontal identity \(2\)-cell \(\id_n^\circ\) is the transpose of this.

The double sub-category of hyperbolic square tangles and braids

Unfortunately, none of the identity \(2\)-cells are hyperbolic; since they constitute \(4n\) parallel loops in a thickened torus, and hence have an essential annulus made by a thickened parallel loop in the same direction. However, there is something we can say:

Definition. We say that a square tangle is a braid if it has endpoints only on two opposing faces, and the (classical) tangle formed by only considering those two faces is a braid.

These work well with composition:

Proposition. Suppose \(\mathcal{T}\) is a square tangle and \(\mathcal{T'}\) is a vertical braid such that the vertical composition \(\cT \cdot \cT'\) is defined. Then, the quadruple of \(\cT\) is identical to the quadruple of \(\cT \cdot \cT'\); hence \(\cT\) is hyperbolic if and only if \(\cT \cdot \cT'\) is hyperbolic.

Hence we may define a double sub-category of the square tangles, with the same 0- and 1-cells, and 2-cells given by those square tangles who are either braids or hyperbolic.